The Best-Laid Plans

A new year, a new challenge for me. After many months of training and preparation, last Wednesday in the wee hours of the morning (1:30am) I jumped off the back of Val Kalmikovs’ boat Meow from New Norfolk (Tasmania) to swim 34kms down the Derwent River – the Derwent River Big Swim. My goal was to swim over 34km and experience the many swimming wonders the mighty Derwent has to offer – night to day, fresh to salt water, cool to cold water, calm to not so calm conditions, rural to industrial to urban landscapes. The Derwent has it all.

Well, the Derwent delivered splendidly, and I am grateful to those who tracked my progress and posted online kind and encouraging words as I swam along the river. After the swim, looking back on these comments they mean a lot to me, as did the phone call from Doug Hughson from the Derwent Big River Swim and the many individual Brisbane swimmers who checked-in over the days following the swim, thank you. Of course, thanks also to Kate Forrester and Alan Rotsey, my on land Hobart supporters, chefs and taxi drivers.

The Derwent River Big Swim is a great swim. I thoroughly recommend it to all willing to put in the time, effort and resources to take on the challenge. My experience was great. It was also a hard life lesson in that no matter how well you have prepared for a swim, open water swimming is dangerous, and things can go terribly wrong very fast, as it did for me. In a nutshell, I got Swimming-Induced Pulmonary Edema/oedema (SIPE) and was pulled out of the water 250m from the finish line.

This post covers my swim, but its main purpose is to encourage open water swimmers and their support crew to understand the symptoms and first response requirements for SIPE. Importantly, SIPE is dangerous, it comes on by stealth, it can affect anyone and can be fatal. Feel free to skip my story and scroll down to the information about SIPE at the end of this post.

I was disciplined in my swim preparation over many months. I completed my swim and strength training programs under professional and successful coaches (Andy Budgen through Pursue Multisport and Vladimir Mravec of Vladswim). My diet and nutrition program was set up with meticulous care and monitored closely by a professional sports dietician, Christie Johnson (Robson) Operation seal blubber went well. I had regular massages with Sam at Sandgate Physio and attended Raw Power Yoga classes a couple of times each week to keep injury at bay. I had completed the requisite 6 hour qualifying swim and did an extra swim in cooler water, just to be sure I could do it. Thank you, Andy, Vlad, Christie, Sam, and Simon, for your help. Thanks also to Trent from Reddog Tri club for welcoming me in your Friday sessions at the Valley Pool.

In the lead up to the swim I was concerned about the cooler waters and spent much time preparing with cold pool plunges and sitting in a chest freezer for 1 to 1.5 hours a session. This concern seemed over the top because during my Derwent swim I did not feel cold. I only felt some coolness in my arms, which makes sense given they are in and out of the water and the air temperature was cooler than the water. Nutrition was spot on and kept me going with Stuart Bettington making sure my feeds were ready and warm each half hour. I kept him busy the whole swim, thank you.

Being a value for money (i.e., slower paced) swimmer I was fortunate to be able to take in the sights, tastes and sounds for much longer than the average swimmer. I steadily swam through from night to day, passing the key sights – two bridges, the paper mill, the zinc factory, cliffs, and so on. By lunchtime the Tasman Bridge was in sight, I was getting super excited about swimming through the pylons to officially complete the swim.

Things were going well. I had behaved well too. I did not grumble or let off a string of F-bombs at feeds, which unfortunately is how I usually behave. We call this person ‘Dark Jackie’, but she seemed to be away last Wednesday. My mind was strong, and I was determined. Yes, I was tired, feeling sore, and breathing was laboured and rattly in the chest. The smacking of the water on my face, particularly on my right side was annoying and meant I was ingesting more and more water. I pushed on and switched from bilateral to single sided breathing on my left. It helped with reducing the water intake. I swam further away from the boat so I could see Val and Stuart more clearly given the smacking waves and my goggles were slightly tinted and foggy. The bridge was near which meant soon I would be out of my togs, in my thermals and sipping on a warm soothing recovery potion. Head down, roll the arms over, kick the legs, breathe, repeat. I’ll be there soon.

At 250m metres from the bridge Val and Stuart (V&S) called me over. Great, we will be talking tactics about how to swim safely through the pylons. Instead, I was yanked out. No discussion. Just yanked out with a life buoy and told it was over. Elation turned to disappointment. How could they do this? I am perfectly fine for someone swimming around 10.5 hours in cool water. V&S said I did not look good. What else could they expect at this point? V&S claimed to be worried as they had spotted concerning signs – slower stroke rate, difficulty speaking, confusion, incoherent speech (basically appearing drunk). A big spew in the back of the boat (sorry Val) and the onset of the after drop just made things even more miserable. A strong sense of failure and disappointment took hold.

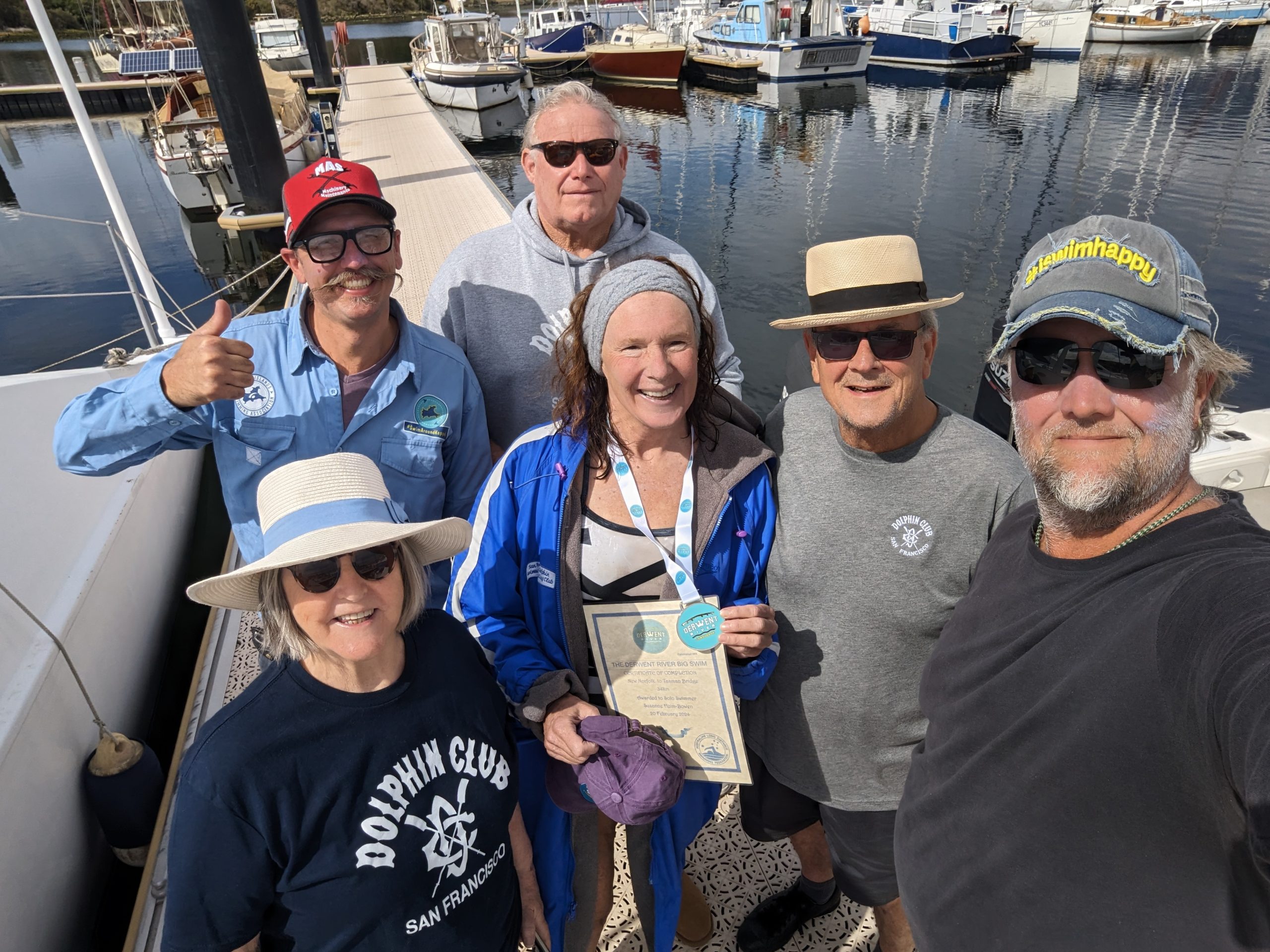

Back at the Marina I was greeted by training buddies and on land support crew, Kate Forrester and Alan Rotsey, who looked at me in horror and called an ambulance (Thank you! Lifesavers). After a long warm shower and changing into my thick woolly clothes I was plonked into the back of an ambulance. My response to this situation was simple: “this is ridiculous. I am fine”. I may have also rolled my eyes a few times. The paramedic took my temperature and recorded my core body temperature at 33 degrees Celsius, said she disagreed with my diagnosis. Low blood pressure, low blood oxygen levels, blue/grey skin colour and other signs suggested I was not as fine as I thought. I guess everyone else seems to have had a point about my state. Perhaps, the swimmer is not the best judge of their own physical and mental state.

So, off to the hospital I go for a 6-hour+ stint in Emergency hooked up to far too many machines that go beep, oxygen streaming in through my nose, cannula in my arm, and my body covered in warm blankets. The verdict: Swimming Induced Pulmonary Edema/Oedema (SIPE). Basically, despite not feeling cold I was hypothermic and had a lot of fluid in my lungs. I was drowning as I was swimming. Getting close to the end, but I am not talking the Tasman Bridge. SIPE is dangerous. It is physiological and there is only one way to deal with it when it takes hold – i.e., stop swimming.

My advice is that all swimmers and those supporting swimmers don’t assume it will not happen to you. It most probably will not happen to you, but it could happen, and you may not be as lucky as I was with the support I had around me on the day. I was only 250m from the finish line and I may have made it to the finish line, but I also may have blacked out and slipped under. No swim is ever worth that outcome.

Being informed of SIPE is easy and takes only a few minutes. To do this I highly recommend watching the following safety video briefings and reading the summary article from Ocean Swims. The first two videos were prepared by the Rottnest Channel Swim Association and the last video features a medical expert with open water swimming experience in the UK.

From the perspective of the swimmer and swimmer support

From the perspective of a medical expert with much Rottnest Channel swim experience in varying ways

From the perspective of another medical expert, a detailed explanation of SIPE and symptoms, and a reminder that many emergency personnel are not familiar with SIPE and what to do. Thus, it is important the swimmer and their supporters can alert emergency personnel that SIPE is a possibility

A basic summary of SIPE, symptoms, first response and recovery

I have made peace with the outcome and V&S’s decision. In fact, I did so by the time I had arrived at the hospital. I recognised I was close to the end, but remain unsure as to which end? I had also achieved the most important goals I had set – swim more than 34kms and experience the Derwent River from New Norfolk to the Tasman Bridge. Swimming past the finish line was simply the icing on the cake. I had worked hard for a long time in the lead up to the swim. I still got to eat my cake in terms of distance and experience, I just missed out on the icing. It also needs to be recognised that pulling a swimmer out of the water is a difficult and distressing call for the skipper and support crew to make. They very much want the swimmer to finish, which is why they are out there for hours bobbing about in the water feeding you sugary drinks and watching you swim. Thank you, Val Kalmikovs and Stuart Bettington.

Will I attempt the swim again? Maybe? Maybe not? I will think about it…

Thanks of course, to the home support crew in keeping me positive and coming along for the ride rather than checking me into a pych ward – Stuart Bettington, Callum Bettington, Douglas Johnathon, Lachlan Bettington, Caiti Bettington, Tara Bettington and Larni Bettington.

– Words by Jackie Bettington